“Imagine no possessions,” John Lennon asked in a famous song. Then wisely added: “I wonder if you can.” I note that Lennon was driving a 19-feet-long Rolls Royce when he composed the song “Imagine.” In fact, he didn’t really drive it; he had a couple of chauffeurs available for that. The former Beatle spent his time in the back seat, where he had a double bed installed along with a television and refrigerator.

No, I don’t blame Lennon. He’s not the only person to take pride in ownership while imagining a property-free world he didn’t actually want to inhabit. Bernadette Peters summed up the pervasive attitude best in the Steve Martin film The Jerk, when she faces the prospect of going from wealth to poverty. “I don’t care about losing all the money,” she declares bravely. Then after a pause: “It’s losing all the stuff.”

Yet, in a strange turnaround, Lennon did imagine the future of his own vocation, the music business. Everywhere else — even in countries that officially embrace communism and the abolition of private property — ownership is flourishing. Everybody wants more stuff. Only music fans have decided they don’t need to own recordings anymore. God bless those altruistic souls: They are happy to share with their neighbors.

Think of streaming like a lending library, but with instant gratification. No need to drive to this library or wait in line to check out items. Everything you want is yours with just the touch of a screen or click of a mouse. Who needs all those bloody albums?

Musicians are suffering under this new economic model. But they tend to blame everything on the rise of digital music and the internet. They see the problem as a format issue, not a question of ownership. In their opinion, the internet turned songs into data, and data just ain’t sexy. Even worse, data is easy to steal, to share, to pirate.

I don’t disagree with this view. The shift from physical recordings to digital tracks has benefited tech companies instead of musicians. The shareholders of the three As — Apple, Amazon, Alphabet — have earned a king’s ransom from music over the last decade, but the content providers (that’s the quaint way musicians are now described by Silicon Valley billionaires) get squeezed to enhance the corporate bottom line.

Music seems to have returned to the medieval era, when starving bards survived by serving the nobility, providing the playlist at a banquet where others were feasting. That’s a fitting metaphor for the new reality in music. The shift in economic models has been rapid and devastating. Apple could now acquire every major record label with just the spare cash in its bank account. But Apple CEO Tim Cook is too smart to do that. He knows there’s no money as a content creator — in fact, his company has worked to ensure that state of affairs.

But there’s another problem in the music business, and it may turn out to be even more devastating for the music ecosystem. The transition from physical to digital music may be less damaging than the shift from ownership to streaming. Most people in the industry are complacent about the latter change. They care about cash flow — they want listeners to pay for streaming. But they rarely worry about how the behavior of music fans changes when they no longer own recordings.

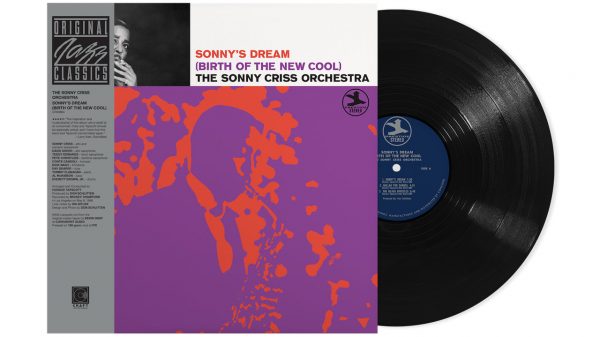

This is a big mistake. The music industry was built on the passions of record collectors. The album wasn’t just a physical object, but a lifestyle accessory, almost a fetish and talisman. People didn’t just listen to their records, they displayed them as quasi-holy relics. The album cover might seem irrelevant — a baby swimming after a dollar bill, a painting of a big banana, or even a blank white slate with only tiny text (The Beatles) emblazoned on it. But to the owners, these served as supercharged personal emblems. The image could change, but the message stayed the same: This is my music. This is who I am.

During the most formative years of emotional development, teenagers would meet and, almost before learning anything else about each other, peruse each other’s record collections. You judged your peers by what albums they owned, and also by those they excluded from their collections. They did the same to you, and teens trembled in fear at the verdicts rendered. Even the furniture collectors used to contain their treasures was revealing, whether old orange crates or ornate cabinets. Parents tended to choose the latter, so we learned to view those with suspicion.

Of course, this was all irrational. Wasn’t it? Music doesn’t sound better when it’s stored in an orange crate. Everybody knows that. Songs don’t change if you borrow them instead of owning them. That’s obvious to all.

But do the geniuses running the major record labels really understand what happens when you remove this irrational pride of ownership from the musical experience? Will fans devote as much discretionary income to music as in the past? Will songs have the same impact on lifestyles and on the mainstream culture?

I note that generations began adopting music as their cohort’s identity immediately after the rise of recordings. The 1920s were called the Jazz Age. The late 1930s became the Swing Era, and in the 1940s people started talking about the Big Band Era. The 1960s was the Age of Woodstock. That doesn’t happen anymore. It’s now the Digital Age or Post-Truth Era or whatever, but music no longer defines demographics the way it did back when people bought albums.

People do not create their identity out of what they borrow. They view themselves in terms of what they possess. That’s why Egyptian pharaohs and other prominent ancients got buried with all their stuff. And if they wanted music in the next life, they sometimes had the musical instrument buried with them — and perhaps even a dead musician who got a fast-track ticket to the great beyond.

When I wrote my book on the history of the blues, I interviewed the pioneering researchers who documented this music and rediscovered the forgotten performers of the past. In every instance, they were passionate record collectors, and their decision to become music historians tended to grow out of their search for rare 78s. My friend Gayle Dean Wardlow started out by going door-to-door in black neighborhoods in Mississippi and asking the residents whether they had any old records to sell. He is now one of the greatest living experts on blues music. Samuel Charters was the first writer to get a publishing contract for a book on traditional blues with The Country Blues (1959), but he too was a collector before he became a scholar. The late Mack McCormick, one of the most brilliant music scholars I’ve ever met, was so focused on collecting that he never got around to publishing the fruits of his research, especially that long-awaited book on blues legend Robert Johnson. Each of these individuals took delight in blues music, but they sometimes seemed to take even more pride in their personal archive of choice 78s and memorabilia. I don’t think the blues revival would have happened — or at least not with the same intensity and impact on mainstream culture — in an age of streaming.

This is why art that can be embodied in a physical object generates more economic value than art than merely exists as an intangible. My wife is a modern dance choreographer, and she sees firsthand how hard it is to build a sustainable financial platform for creative works that exist as ephemeral experiences. The same is true of other creative fields — go check out the list of the most expensive photographs sold last year, and see how many were physical prints versus digital rights. You will find that every one on the list was a physical object. Even in the internet age, the passionate art lover wants to own the work of art. I suspect that some smart scholar could even measure and quantify the value added to art when it becomes objectified.

Critic Walter Benjamin may have anticipated the current situation 80 years ago when he published his influential essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Art has a more beneficial social impact, he argued, when it is no longer a rare item controlled by wealthy elites. Because of his pronounced Marxist sympathies, Benjamin might well have looked forward with approval to a time when no one owns the songs they hear. But I note that Benjamin showed even more enthusiasm in a lesser-known essay, entitled “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting.” Here you get a sense that this esteemed thinker’s own intellectual development was built on the foundation of his zeal for book ownership. Like John Lennon, he might praise a world with no possessions, but could hardly envision living in it.

This connection between ownership and passion is vitally important to the economics of music. If you eliminate the former, you erode the latter. Yet there’s an even bigger danger to a music ecosystem that gives up on ownership.

What happens when the mega-corporations who run the streaming services decide to delete a million songs that aren’t generating sufficient profits to justify their storage costs? Or ten million? Or maybe whole genres — 12-tone-row music, Native American chants, 1920s jazz, etc. — because they just don’t draw a meaningful audience?

Just look at how ruthlessly Netflix has reduced its offerings to lower its costs. Those old movies didn’t justify their upkeep anymore, so they got deleted. Or look at how libraries are getting rid of books to make space for more profitable cafés. If you don’t think it will happen in music, you don’t understand economics and the motivations of profit-driven companies.

Much of our documentation of the past exists today because some private owner decided to save a cultural artifact when institutions and businesses saw no value in it. The record industry isn’t very old, yet that has already happened with its products. Many historic recordings exist today only because a loyal fan held on to the disk. The same is true of cinema. Ninety percent of all films made before 1929 are lost to us. In many instances, collectors held on to prints when studios did not. It is sobering to consider that the very companies that made these movies didn’t take adequate steps to preserve them.

Look at almost any other field of culture and you will find the same phenomenon. What we take for granted today will disappear tomorrow. And the internet brings with it the potential for cultural destruction on a scale previously unfathomable. Do you want to trust the preservation of music to Apple and Google? Do you think they value it the same way you do?

Remember those pharaohs I described above — the ones who were buried with their musical instruments and sometimes the musicians too? We need to give them some credit. If they hadn’t been such passionate collectors, we would know very little about the music and culture of their times. We need to be more like them. Collect like an Egyptian!

But it shouldn’t be entirely left up to us. The record industry also has a role to play in bringing back music ownership. The labels need to embed music into exciting and alluring physical objects. Perhaps this is a return to vinyl, but I have a hunch that it is more likely to be a kind of high-tech “enhanced” vinyl or some other platform that doesn’t even exist today. As other industries have done, the music business needs to develop more clearly demarcated “freemium” and “premium” options for its customers. Indeed, this would have already happened if the record industry still invested in R&D the way it did back when RCA developed stereo sound and Columbia pioneered the long-playing album. By ignoring tech innovation, the labels created this mess. But by returning to the core principles that gave birth to the recording industry, they can still fix it.

In the meantime, fans should show their commitment to their favorite artists by buying their music. Don’t just stream, but own. As John Lennon once said: It’s easy if you try.

Ted Gioia is a leading music writer, and author of eleven books including The History of Jazz and Music: A Subversive History. This article originally appeared on his Substack column and newsletter The Honest Broker.

Scott

May 5, 2022 at 12:34 pm

Great article.

I want a purchase button to be provided by my streaming service. I pay for the album while connected to emotional response of listening and then it downloads to my Mac or pc.

I also want a give button, give 1$, 2$, etc.

I’m currently purchasing more used music and new artist merch.

Cheers, SL

ORT

May 6, 2022 at 2:20 am

A lot of today’s “music” is any thing but. A lot of music from the past should be buried because it is long past its expiration date. A lot of the so-called “Blues” just plain suck. A lot of early rock ‘n’ roll sucked. A lot of poopular music sucked. Even some Jazz sucks, especially so that extemporaneous scales playing drivel that so many critiques wax on and wax off over. UGH!

Just because some one named “Art” wrote/composed some thing does not necessarily make it a work of art. If I want some thing I buy it but only if I can afford it comfortably. I do not think I have to support that which I do not care for, be it music, art, film, what ever.

I have been around since its inception and I think for example, PBS is a farce. Support the Arts if you wish but do not take tax money and dole it out to “poet lariats” (think about that one), beatniks, cRap “singers” or even the next Sinatra (although I do not for see that ever coming to pass, just as there will never be another Ella.

You touch on an “enhanced vinyl”. Do not be a ridiculous sounding board for that pipe dream. Do you know what a pipe dream is? It is the “dreams” induced by an Opium den and the smoking of said drug via a pipe. Stupid and use less. Oh to be certain there are other definitions but none as truth full as that one.

Another reader here said it best. The CD is a superior version of vinyl and look what happened to it. “What is that?” I hear you say…frAudiophiles are what happened. Scum that are the Sadducees of audio. They strain at a digital bit and swallow a lie. And then spit out their lies as Holy Rote. To Hades with that crap! Be happy with that which we currently have and if the market truly demands it, another physical medium will come to pass.

And when it does, the frAudiophiles will do just that. PASS. Whiny, ungrateful maroons, the lot of them. And no, I do not think that of Ian and Friends. They are for the greater part, writers, and good ones.

Believe me, I know typing when I read it. And if some thing is worth collecting it shall first be coveted by the memory, the heart and soul of each of us. The soundtrack of my life is filled with more songs than I could ever afford to purchase and so I buy the ones that mean the most to me. I am not some Pharaonic collector of either music or equipment. I will not take them to my grave as the Pharaohs did.

My Ima taught me thus. No man dies alone who has the memories of a lifetime with him. To that I would add and the sound track to accompany them.

ORT

Dennis

September 21, 2022 at 5:32 pm

ORT, This is a very audiophile rant. Go ahead and say it, “I am an audiophile and I am proud.”

ORT

September 23, 2022 at 11:43 pm

Thankyewveruhmuch, sir!

ORT

danny

May 6, 2022 at 8:24 am

Ownership?

If I buy digital files and download them to my personal server, is that ownership? Or does it mean physical ownership?

Scott

May 6, 2022 at 9:01 pm

Digital files on your PC = ownership

Ian White

May 7, 2022 at 12:01 am

Scott,

Correct. Versus streaming which is a rental.

Ian White

H. Fivelsdal

May 29, 2022 at 3:22 am

“The music industry was built on the passions of record collectors. The album wasn’t just a physical object, but a lifestyle accessory.” Why is this no longer the case? One can still collect music in either digital files or CDs, vinyl, cassettes, etc. Also, back in the day we also would borrow and lend records, so we had the equivalent of streaming. I would not usually buy records that a friend or significant other owned since I could easily borrow them – unless it was something I wanted to listen to repeatedly.”There’s something happening here. But what it is ain’t exactly clear”.

I agree that streaming isn’t good for the creative artist but that has more to do with power dynamics in the record industry than it has to do with technology. I think that Ted is onto something when he describes the lack of a subculture in our society (not in this article). That is why the younger generation does not value music as a physical object worth collecting. If they did, Spotify would not make much money. Music used to stand for something more than motivation to work out to at the gym.

Steve H

September 14, 2022 at 7:47 pm

I think engagement with artists is better than ever. What is the only good use of Twitter? Staying in touch with artists. Add Facebook and other social media and you have something. A bit different from the past but the world has changed why shouldn’t artist engagement change with the times?

Craig

November 28, 2022 at 7:17 pm

The ownership of listening rights on hard media is a phenomenon of the last 100 years. Prior to this, all music was live and in real time. Streaming offers something of a return to this earlier, real time state but only if digital copying is eliminated and no physical media is produced. The latter probably cannot happen.