Reprinted with permission from Knowledge@Wharton

In the world of web browsers, it's beginning to look a lot like the 1990s. Back then, the Internet was just starting to become an integral part of daily life and Netscape's Navigator and Microsoft's Internet Explorer vied for dominance in helping users surf the web. By the end of the decade, Microsoft emerged the winner and Netscape faded into dotcom history.

This time around, the browser battle includes an increasing number of competitors, most notably Internet Explorer, Mozilla's Firefox and Google's Chrome. But players such as Apple's Safari and newcomers like RockMelt, a start-up that promises to integrate web browsing with social networking, are banking on innovative features to stand out in a sector where users are reluctant to change — or are unaware of myriad options beyond their browser of choice.

What's behind the browser renaissance? Wharton experts attribute the new interest in part to cloud computing, which allows data to be hosted on remote servers and run on demand over the Internet; and mobile computing, which has put Internet-connected devices into everyone's hands. Meanwhile, some popular browser engines — the component of the application that turns the underlying HTML code and formatting instructions into the final web pages that users see on their computer screens — are now open source, meaning that anyone is free to use, change or enhance the software. For example, RockMelt — which began offering beta access on November 8 — uses the underpinnings of Chrome and integrates services such as Facebook and Twitter. A number of other browsers are based on Webkit, an open source project originally spearheaded by Apple. According to Kendall Whitehouse, director of new media at Wharton, open source has dramatically lowered the development costs involved with building a browser and "makes it much easier for a company to focus its development efforts on value-added services. [RockMelt] is a good example of open source components making innovation possible."

As a result of these open source browser components, newcomers can enter the market without building technology from the ground up. Instead, players like RockMelt can focus on new features in search of the perfect browser. "The ideal browser to me will be customizable, learn about my preferences over time, allow me to easily turn on and off social services and segment 'friends' for use in those services, and share my browsing history across multiple devices," says Shawndra Hill, an operations and information management professor at Wharton. "The browser will most importantly help me to find the pages I am looking for on the web efficiently and effectively."

Browsing Goes Social

When Google launched Chrome in September 2008, it spurred a new wave of development of faster, more lightweight browsers. According to RockMelt CEO Eric Vishria, browsers are undergoing another innovation spurt — in his company's case, one that is tied to creating an experience that mirrors the way people use the web today. "We want to bring the notion of sharing, identity and having your friends built into the browser," he says.

In addition to faster search capabilities, RockMelt has a sharing function built into the browser. Once users give RockMelt access to their Facebook accounts, the browser allows them to see which friends are online and provides one-click access for updating Facebook, Twitter and other sites without navigating away from the web page they are on. The data is stored in the cloud, so it can be accessed anywhere on any computer.

RockMelt's approach has already attracted the interest of a few veterans of the earlier browser wars of the 1990s. The start-up has received roughly $10 million in funding from investors such as Andreessen Horowitz, the venture capital firm run by Marc Andreessen and partner Ben Horowitz. Andreessen was co-founder of Netscape, which first popularized the web browser in the mid-1990s.

"The browser got ignored too long in the late 1990s and early 2000s after [Microsoft's Internet Explorer] crushed Netscape. No one else was willing to take on Microsoft until Google decided to dedicate resources towards the browser [first, indirectly through Firefox and later through Chrome]," notes Kartik Hosanagar, an operations and information management professor at Wharton. "The success of Firefox and then Chrome has showed that there was ample room to innovate."

Indeed, scarcely a week goes by without something new in web browsers. Mozilla has Firefox 4 on tap for 2011 and promises speed enhancements in the new release. In addition, Mozilla is experimenting with social networking features to make sharing web pages easier. Microsoft's Internet Explorer is embracing HTML5, the next generation of web's page description language. Apple's Safari and Opera, the browser created by the independent Norwegian company of the same name, have become dominant for browsing on mobile phones. Google continues to make frequent enhancements to its Chrome browser.

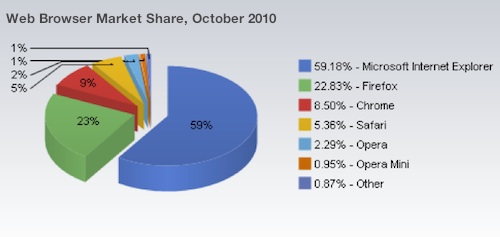

As a result, global market share has been split among a handful of leading players. NetApplications, a web applications and analytics firm, estimates that various versions of Microsoft Internet Explorer control 59.2% of the browser market, followed by Firefox at 22.8%. Google's Chrome captures 8.5% of the market and Apple's Safari has 5.36%. Opera has 3.2% market share including its desktop and mobile browsers.

When Google launched its Chrome in 2008, the strategy was to create a lightweight browser that could quickly run increasingly complicated web applications like Google Maps and Google Docs. According to Whitehouse, Google's Chrome "sparked another round of browser development. Microsoft woke up and focused renewed development effort on Internet Explorer." Indeed, Chrome kicked off a race between Google, Microsoft and Mozilla's Firefox to be the fastest browser on the web.

The download page for Chrome describes the web browser as "arguably the most important piece of software on your computer." And many experts agree that the browser has only become more crucial in recent years as buying new computer software became less about a trip to the store and more about visiting a website and clicking the "download" button. Browsers — whether enhanced by plug-ins like Adobe's Flash Player and Microsoft's Silverlight or implementing the latest HTML5 features — are now able to run sophisticated software programs including video, games and business applications "In a cloud computing-based environment, software becomes service-driven rather than a shrink-wrapped product," notes Andrea Matwyshyn, a Wharton professor of legal studies and business ethics. "Off-the-shelf software is becoming a thing of the past. The browser has become the focal point."

In the 1990s, one notion was that the browser would become the de facto operating system. That prediction never panned out, although Whitehouse acknowledges that the browser plays an increasingly expanded role on users' computers. "While an operating system is still important to handle routine hardware functions, the browser — and Internet-connected platforms like Adobe's AIR — play an increasingly pivotal role in the way the user interacts with software applications, minimizing the role of the underlying operating system," he says.

But not everyone considers the browser a big deal. Hosanagar thinks current trends indicate that the software is more important, but "I won't take the extreme position that it is a replacement for the OS." Wharton marketing professor Peter Fader compares intense competition in the browser sector to a pillow fight: "There's not a lot of meaning there, and the browser is just a small part of the equation" in achieving dominance on the web.

Indeed, in a recent story in Wired magazine, editor Chris Anderson argued that the world wide web is nearing extinction and that surfing will soon be replaced by downloaded apps. "All of the Internet connections are still there, but people want to get where they want to go quickly," Fader notes. "A browser is a layer between that. Apps get you right where you want to go. What does a browser mean on the iPhone or iPad? No one spends time on a home page on the iPad. You have a bunch of apps and you choose one."

RockMelt's Vishria, however, disagrees with the idea that the web — and the browser — are operating on borrowed time. "The web is the primary way we get news and information, and the browser is the primary way we find anything," he maintains. "Our job is to create a much better browser experience."

The Next Generation

It remains to be seen whether RockMelt will be successful, but experts at Wharton say the idea of browsers incorporating social networking data and other new features is a natural progression. According to Hill, the next generation of browsers will take existing systems from Microsoft, Google and Mozilla and build on them to create niche software focused on specific tasks. "It appears that RockMelt is a more feature-based add-on to Chrome as opposed to a full-fledged browser," she adds. Vishria does not dispute that argument. "Because Chrome is open source, we can benefit from all the speed improvements and add what we're doing on top of it," he notes.

While RockMelt initially focused on adding Twitter, Facebook and news updates in its quest to build a more social browser, Vishria says there will be extensions for e-commerce and other activities. The Facebook obsessed "will love RockMelt, but others may refrain," Matwyshyn predicts. "Certain browsers will fit audiences better." For instance, Matwyshyn suggests that other browsers in the future may be tailored to specialized markets, such as e-commerce or gaming.

But Hill and Matwyshyn warn that privacy concerns related to providing the information needed for cross-platform integration with Twitter or Facebook could hamper adoption of RockMelt. In addition, it is not clear whether a wide audience will want social media and browsing to be integrated. Vishria says RockMelt will not share browsing data with other networks. "We're not running an ad network, and there's no incentive to share data," he notes.

Another unknown is whether any of the next generation browsers can capture enough market share to make money. Whitehouse notes that most of the major browser vendors — Microsoft, Google and Apple — make revenue from other products in their portfolio. "For these companies, the browser's main value is to drive users to the other services they offer — and they can readily monetize." Some browser vendors also garner income by selling their search boxes to companies like Google and Microsoft, who bid to become the default engine used when a user looks for information. For instance, Google accounts for most of Mozilla's revenue.

Vishria's plan to make RockMelt profitable includes adding multiple services and charging companies to be the default providers, rather than just selling rights to the search box. He names e-commerce as one channel that is ripe for such an approach. However, Vishria acknowledges that RockMelt, which only recently launched its beta, needs to acquire a critical mass of users first.

The biggest risk to RockMelt and other entrants may revolve around larger players adding similar features. "These new 'social' features can potentially be incorporated into the top three browsers," Hill points out. "Likewise, if Facebook later decides to enter the browser game, they could easily incorporate social features to browsing."

According to Wharton management professor David Hsu, it is doubtful that the likes of Mozilla, Google and Microsoft will shift gears to take on a start up. "From a new entrant perspective, RockMelt is counting on Google to not mess around with its market too much. It's likely that the incumbent companies will monitor RockMelt, but they won't reorient what they do to take it on — at least in the near term."

Startups like RockMelt will also have a tough time breaking through consumer inertia. Experts note that it takes a lot to get consumers to try a new browser. "Most people don't care what the browser is," Fader says. "Unless there's meaningfully different functionality, browsers are a commodity."

Hosanagar agrees that consumers generally will choose to stick with what they know instead of moving to a new web browsing interface. "I doubt the browser market will be highly fragmented in the long term," he adds. "I suspect that we will have a few major players covering over 90% of the market, just like in search."

But Vishria remains undaunted by the odds. Browser market history is on his side, he says, noting that Chrome did not exist two years ago, and Mozilla's Firefox managed to grab market share from Microsoft. "The history of the browser market shows that companies with a better product can come in and disrupt."

Reprinted with permission from Knowledge@Wharton, the online research and business analysis journal of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania