Audio is just a hobby. It’s not overtly changing the world, although I think many of us would argue that their world is a much better place because music is in it. Our brains are hardwired to distinguish music from noise, and all cultures have their own form of music. Many studies link music listening to human health benefits, cognitive performance, lowering stress, and improving mood.

So perhaps we should not discount ‘sitting around and listening to music’ as anything less than taking excellent care of ourselves.

I started writing this guide about 6 years ago when I seemed to be answering a lot of general interest questions about audio gear. I’m in my 40s and am one of ‘those guys’ that has perpetually toted around a full-sized stereo from the time I moved into my first university dorm room.

The recent vinyl renaissance has started a lot more people thinking about finding space for a stereo in their lives. To these folks, the iPod dock, or smart speaker, is starting not to look sufficient anymore. Times change. I watched vinyl go away as I bought CDs, minidiscs, SACDs, and eventually digital downloads. Then I happily jumped aboard the record train again when it came rushing back.

Like many, I don’t have the financial luxury of being able to afford brand-new, top-of-the-line equipment (regardless of my predilections). As such, I want to state something emphatically first thing.

It is NOT necessary to spend a ton of money on the gear to enjoy music.

Truth be told, I just purchased an inexpensive, waterproof, Bluetooth speaker from the latest Amazon Prime Day deals. For under $30 the amount of technology and sound quality jammed in something the size of a can of pop is astounding. Is it high-fidelity? Absolutely not. Will it replace my stereo? Nope. But does it allow me to take and enjoy music anywhere (showering, working in the yard, to the beach)? Heck yeah.

The focus of this article is to profit from my mistakes (and occasional good choices) and to help make informed decisions when purchasing audio gear. Maybe you are interested in getting into the audio hobby, or perhaps you just were given your first record and you have no idea what to do with it. Hopefully, this will help.

Stereos and Headphones

Currently, seemingly opposing segments of audio are flourishing at the same time. In one case, we have the pressure to downsize and to accept fidelity compromises in the name of convenience and form factor. Yet in the world of smart speakers and soundbars, vinyl record sales have triggered the recent return of record players and full-sized home stereos to match.

In portable audio, smartphones have won their battle with the iPod and the now-defunct 3.5mm headphone jack. Yet, with the rise of Beats (like the brand or not) there is now a revival of headphones and the birth of ultra-high-end personal audio.

The more the general population moves towards convenience devices and formats, the more it seems to push music lovers to adopt ever more specialized audio products. The basic mp3 player has disappeared, however, it has evolved to become a plethora of ultra-high fidelity DAPs (Digital Audio Players).

The niche market is alive and well. As consumer electronics have become more digital, interest has exploded in analog devices. Tube amplification has become commonplace again in full-sized stereos and headphone amplifiers. This archaic technology disappeared from the western world about half a century ago, but tube manufacturing has survived and blossomed in Russia and China.

The rise of Chinese manufacturing of high-fidelity audio equipment has heralded a tremendous change. Known colloquially as Chi-Fi, it is responsible for high-quality, low-priced products flooding the world market. From In-Ear Monitors (IEMs) boasting many drivers, to digital amplification and devices, to the manufacture of tube amplifiers, Chinese manufacturing has taken over the audio world. All of a sudden, technological marvels are affordable for the ‘everyday audiophile’.

It’s seriously never been a better time to get into the audio hobby.

The Stereo Chain

To understand what is needed to listen to music, it is important to define its elements. In essence, a stereo system consists of three main parts:

Source → Amplification → Speakers/Headphones

Each of these parts may be separate, or in the simplest cases, such as a desktop radio, they may all be contained in a single component. If all are separate, they are connected with specialized cables.

We will take a look at each of the three elements in turn, and at the cables that connect them, but first things first. The music!

The Music

Are you a collector? If so, you should spend the majority of your budget on the music itself. What’s the point of having achieved audio playback perfection if you’ve got nothing to play on it? Besides, in these crazy times, musicians need all the support they can get. In recent years, the bulk of the musician’s income has come from live concerts. And in 2020, this simply isn’t happening anymore.

So, get out there and support your favorite musicians and local record stores with CD and vinyl purchases. Believe it or not, cassette tapes are even starting to appear again. New music is available in basically any format you could want.

Of course, streaming services are a great budget option to have access to a HUGE library of music. You don’t get to keep it, but for many folks, streaming may provide the perfect combination of affordability and absolutely no physical storage space required.

The quality of streaming services is almost uniformly excellent and some even provide high-resolution audio files (besting CD quality).

1. The Source: Analog and Digital

Ah… the age-old debate around audio quality. “Nothing sounds better than vinyl”, say the analog purists. “High-resolution digital files can’t be beaten”, argue the digital adopters. Should music be ‘smooth and musical’ or should it be ‘detailed and precise’? “It’s the way the artist intended it!” is an argument you will hear from both sides.

Traditional thinking here is garbage in = garbage out. In other words, your stereo can only sound as good as the music you are playing on it. If something is recorded poorly or played back crudely, it doesn’t matter how expensive or great the rest of your gear is, the result is not going to sound good.

Fair enough. It’s hard to argue with that logic.

Analog Audio

Analog sources include vinyl, 8-track, cassette tape, and reel-to-reel tape. You will find fans of them all, who believe that having absolutely no digital recording, mixing, or playback in the chain is audibly superior. I have no great love for tapes of any sort these days.

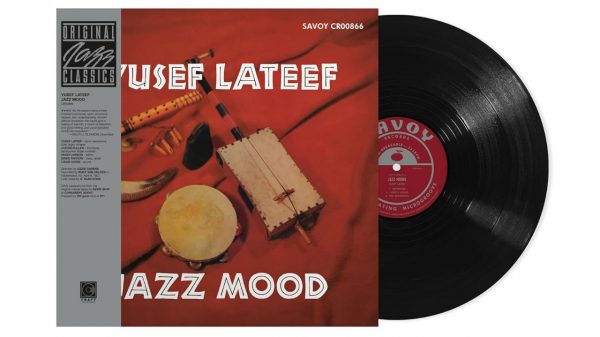

On the other hand, I like vinyl records. Vinyl is immensely satisfying to purchase, to give as gifts, to open, and to play. Not to mention that it satisfies the collector in me. It changes music listening from a couple of clicks on a device or a computer, to an interactive ritual. Vinyl has got me back into perusing used record stores, a much-loved pastime for my younger self.

In the world of the intangible digital, vinyl is a wonderful archaic magic that you can hold in your hands. A tiny diamond-tipped wand vibrates as it travels along a half-kilometer long spiral groove cut into a piece of plastic and music comes out. Shazam, that’s real magic!

Are vinyl records inherently better than digital sources (CD, DVD, mp3, or FLAC)? Even if you completely ignore the crackle and pops of dust and the (almost inevitable) scratches on records, the answer is no.

Poorly recorded or mastered music, regardless of format, sounds bad (and vice-versa). The Civil Wars self-titled album on vinyl (even though it is a heavy-weight ‘audiophile’ pressing) was the first good (bad?) example of this that I’ve run into. It sounds awful (muffled with limited range and dynamics) compared to the digital version of the same album. On first listen, my wife and I were concerned about hardware failure in the record player because the sound was so immediately noticeably inferior.

On the other hand, I have many well-made records, CDs, and digital files that sound just fantastic. The short-lived DVD-Audio and SACD (Super Audio CD) digital formats are (with properly mastered material) fairly jaw-dropping in their improved sound quality over the standard releases. The Barenaked Ladies: Maroon, and SEAL: Best 1991-2004 are great introductions to the potential of this medium – they take pop music you likely are familiar with and surprise the listener with a sound so much more engaging than their CD equivalents.

Turntables and records are physical objects. They rely on a physical interaction between the needle (stylus) and the grooves cut into the record (no lasers nor computers here). Therefore, the quality of the needle makes a difference in the quality of the sound. A mid-range stylus sounds better than a cheap one. I can only assume that a high-end stylus continues the trend although my personal experience tops out at around an approximately $200 model (Ortofon 2M Blue) that sounds better than its half-price, younger brother Red (which is no slouch).

Expect to spend at least $50-$100+ for something satisfying and keep in mind that the stylus does wear out with use (perhaps lasting about 1000 hours when properly treated). I should also mention that they are fragile; misuse will irreparably damage a stylus (and potentially your records).

There are tons of new record players being manufactured, but a used model in good shape can be had very reasonably (often for the price of a new stylus) if you look around.

Digital Audio

The digital audio world was originally built on compression and compromise. That is, finding ways of using less storage space to digitally store an album while trying to minimize the amount of audible degradation. To these humble beginnings, the lossy format mp3 was born.

The mp3 has always been much maligned by audiophiles due to the sound quality depreciation inherent in higher-compressed (smaller-sized) files. This is less of an issue these days as recording algorithms have greatly improved, and storage space keeps getting less expensive.

Popular thought is that a high-quality mp3 (320 kbps or above) is (virtually?) indistinguishable from the non-compressed version. My feeling is that it isn’t worth taking the risk of lesser sound quality, to save a little (inexpensive) storage space. Rip and store digital files in lossless (uncompressed) formats such as FLAC or Apple’s ALAC. If you want to put a compressed version on a portable device to save storage space, it is easy enough to convert the perfect uncompressed version to whatever is desired.

Computers tend to be noisy devices more focused on computing power than on outputting perfect audio. A decent external DAC (Digital to Analog Converter) connected by USB to the computer and via analog RCA cables to the stereo amplifier is the best way to experience excellent quality playback of digital files.

A DAC setup is (at the very least) equal in sound to a good CD player but with all the convenience inherent in digital music library management. Because of this, digital files have essentially replaced the CD in my life.

A DAC is inside every device that plays digital audio and has a headphone jack or speaker outputs. They don’t have to be expensive to have excellent performance. Perhaps the greatest example of this is the inexpensive ($10), tiny Apple Lightning to 3.5mm adapter.

DACs are computing equipment, and like all technology, advances mean that newer (less expensive) models can be equal or better in performance than older very expensive options. In the used market, I’d suggest shopping for one that is only a few years old, as newer DAC models support higher resolution file playback and may be more compatible with newer operating systems.

Digital Files

DACs convert digital files to analog audio. While that is simple to grasp, the finer points can get a bit confusing. To understand digital files, we have to wrap our heads around how digital files are created. Several terms always come up:

- Frequency

- Sample Rate

- Bit Depth

- Bit Rate

As you’ve likely seen before, sound is represented by a continuous analog wave. Each wave has a peak and a valley called a period. Frequency is measured as how many periods go by in a second.

To convert that analog wave into digital, the wave is measured at intervals of time. This process is referred to as the Sample Rate and is measured in kHz. The amount of data that is saved per sample is known as Bit Depth (measured in bits). Higher sample rates create a more accurate recording, while bit depth is responsible for the dynamics and detail of the reproduction.

Bit Rate (measured in Kbps) measures bandwidth (amount of data over time) and determines the file size and the overall quality of the digital file.

The CD standard is 16-bit/44.1 kHz (Bit Depth/Sample Rate). This standard is based on the Nyquist Sampling Theorem that states that it is necessary to sample at a rate that is (at minimum) twice the limits of human hearing to capture all the information. Since human hearing is generally stated as 20Hz – 20kHz, the original designers decided that adding a bit and doubling it was sufficient to capture what humans can perceive (22kHz *2 = 44kHz).

Dynamic range is essentially the difference between the lowest level noise in the system and the loudest possible sounds. In analog systems, the high-level saturation will result in distortion or clipping. The CD standard 16-bit depth captures a dynamic range of 96dB.

Digital enthusiasts are often obsessed with ever-increasing numbers and modern DACs are reflecting this trend. Inexpensive DACs are not only capable of the CD standard of 16/44.1, but 24- and 32-bit support, combined with sample rates up to 768 have become commonplace.

24-bit digital audio has a maximum dynamic range of 144dB and 32-bit has a maximum of 192dB. But how much is too much? At what point can we no longer perceive differences and we are just chasing theoretical maximums?

It’s important to realize that vinyl music lovers are often obsessed with audio quality, yet “vinyl microgroove phonograph records typically yield 55-65 dB, though the first play of the higher-fidelity outer rings can achieve a dynamic range of 70 dB.” — Wikipedia

So, while it’s easy to get caught up with a bad case of digital upgradeitis (a totally real audiophile affliction), we do need to remember that CDs (and yes, even records) can sound excellent, even if their ‘numbers’ don’t look like they should.

By all means, buy a DAC that looks to be ‘future-proof’ with wide file format support, but realize that subjective quality differences in DACs are relatively small, even with differences in decoding chip or design topology.

2011 MacBook Air

DIY Millett NuHybrid amplifier

Modified BottleHead Crack OTL amplifier

xDuoo XD-05 Plus portable DAC/Amp

Topping D10s DAC

Chord Mojo portable DAC/Amp

Soncoz LA-QXD1 DAC

DIY input switch box with VU Meters

Hagerman Tuba amplifier

2. Amplification: Tubes and Solid-State

Pre-1970 the standard for amplification used glass vacuum tubes. After that date, solid-state amplification (using components like diodes, transistors, etc.) became more common. On paper and in theory, the two approaches should yield similar results, but the audible differences can be quite noticeable.

Tube amps are generally more expensive in initial cost and to operate (because you need to replace the tubes occasionally), while solid-state amps are generally less delicate and more reliable. Many music lovers, however, feel that tube amps yield a warmer, more musical tone and more musical-sounding distortion.

Solid-state amplification may be more clinically accurate in sound reproduction, yet the distortion inherent in tube design may create a more pleasing sound to some ears. As with everything to do with stereo music playback, the determination of ‘better’ is in the ear of the listener.

The process of tube rolling (trying out different tubes, typically from different manufacturers, in the same spot in an amplifier and selecting the one that sounds best) is flexibility unique to tube amplification. You typically can’t just easily swap in a different component in a solid-state amplifier, although some do use sockets to allow for user-replaceable operational amplifiers, leading to “op-amp rolling”.

The different sounding tubes act as a type of hardware equalizer to further customize the sound of the amp to the owner’s preference. Unsurprisingly, this can quickly become a very expensive game of trial and error, especially if the owner becomes obsessed with chasing all the variations.

For very high-power output, solid-state is typically the way to go, as tube amplification has usually relatively low wattage. Using a hybrid model of tube pre-amplifier stage (with the tone, balance, and source controls) and pairing it with a solid-state amplifier gets around this problem by yielding the desired tube-sound and solid-state power.

Speaking of power, how much amplifier power is required for reasonable listening levels? Does a low power amplifier equate to low volume and unsatisfactory performance?

Amplifier Power and Music Volume

When I grew up, wattage was the number one ‘selling’ point for most full-sized amplifiers and speakers. Likely in an attempt to simplify marketing, amplifier wattage has been misconstrued to equate to playback volume and audio quality (and the theory that more is better – sort of like megapixels and cameras). Bigger numbers always seem to cost more and numbers are easy to sell – A has more than B so therefore A must be better.

Volume is a function of SPL (Sound Pressure Level) measured in decibels (dB). Speakers are typically rated for maximum wattage they can handle and the SPL as something like “90dB @ 1W/1Meter”. In plain terms, this means that at a distance of 1 meter from a speaker that is receiving a 1-watt signal, the sound pressure level is measured to be 90 decibels.

Headphones are similarly rated in sensitivity (dB) and impedance (Ohms), but not, of course, at a distance from the ear. This combination determines what the amplifier requirements are for a given set of headphones. Often higher-end headphones require more amplification than a portable device like a smartphone can deliver.

Note: You may run across the statement that “the first watt is the most important”. This refers to the fact that most listening is typically done with an amplifier only running at about 1 watt of power, so it would be preferable if the amp sounded its best at this level.

Speaker efficiency exists in a fairly small range. For speakers, 87-90dB is fairly common. Inefficient planar speakers (such as Magnepan) may be down around 86dB. An uncommonly efficient speaker may be as high as around 105dB.

Note that 87dB is reasonably loud (lawnmower), 97dB is very loud (motorcycle), and 107dB (shouting in the ear) would cause most people pain and potential hearing damage in only a few minutes. Again, this range is narrow.

It takes twice the wattage to get a 3dB increase in volume level. This is the key amplifier takeaway, and this is why speaker (and headphone) efficiency is so much more important than amplifier wattage when determining usable listening levels.

A 3dB increase isn’t that noticeable (not very audible). To notice a doubling of perceived volume level it takes about a 10dB increase.

Therefore, a 2-watt amplifier will only output 3dB more than a 1-watt amplifier. And that means a 20W amplifier will only output 3dB more than a 10W one. The same is true for a 1000W amp over a 500W amp. Talk about diminishing returns.

There is another way to achieve dB and it has nothing to do with a more powerful amplifier, namely: speaker sensitivity. Amplifier

Power (Watts)Low

Sensitivity SpeakerMedium

Sensitivity SpeakerHigh

Sensitivity SpeakerVery

High Sensitivity SpeakerSPL – 87dB @ 1W/1M SPL – 91dB @ 1W/1M SPL – 96dB @ 1W/1M SPL – 105dB @ 1W/1M 1 87 91 96 105 2 90 94 99 108 4 93 97 102 111 8 96 100 105 114 16 99 103 108 32 102 106 111 64 105 109 114 128 108 112 256 111 115 512 114

With the 87dB speaker, you will need approximately a 250-watt amplifier to achieve the same volume that a mere 32-watt amplifier will reach with the 96dB speaker. Keep in mind that 250-watt amplifiers and speakers that can handle this are relatively few and far between.

In the real world, the difference between a 75W and 100W amplifier is practically indistinguishable, while a 6dB increase in speaker sensitivity has an enormous impact. For normal listening levels, high to very high-sensitivity speakers can be driven to extremely loud levels with only a handful of watts. In the headphone world, it only takes milliwatts to drive efficient headphones, and a 6W headphone amplifier is considered an absolute monster.

This phenomenon allows us to understand how very low wattage tube amplifiers are actually usable. Their owners will pair them with sensitive speakers for the best results. My daily music system uses a 17.5 WPC tube amplifier driving 96dB speakers and I can attest that high volume is easily achievable with this setup in a medium-sized room. There are many folks out there that use a so-called ‘flea-powered’ 2-5 WPC tube amplifier with very sensitive speakers to great success.

There is a school of thought that speakers (especially tweeters) are damaged by low power amplifiers being driven to distortion and clipping. Although this is disputed by others who claim it is only the excess heat generated in the speaker’s voice coil (which is created by high levels of amplifier power) that will burn them out. I wouldn’t worry too much about it, especially if you aren’t commonly listening to music at the top end of your amplifier’s power.

Project Debut turntable with custom LEDs under the acrylic platter and Ortofon 2M Blue cartridge

Mii B031 APTX Bluetooth Receiver

Micromega MyDac DAC

Marantz SD4000 tape deck

Marantz 2245 Receiver in DIY wooden sleeve

Silverstone HTPC case with a spare Marantz logo

Pioneer DV-563A SACD/DVD-A/CD/DVD player

Technics SH-8046 EQ/Spectrum Analyzer

Tube Clock from Etsy

Dynaco ST-35 Modded EFB Tube Amp

Marantz SR4002 7.1 Receiver

Old IKEA stand with no doors or back

4 120mm fans for active cooling

Klipsch KG 5.2 with Bob Crites diaphragms

Mix of Paradigm and PSB wall mounted surround speakers for TV

All bought used and repaired / upgraded by me. Very much bought or traded for on a tight budget.

The vintage gear is solely for 2 channel music listening. 2245 serves as a preamp for the ST-35.

Vintage vs Modern Components

Have you heard it said that vintage (pre-1980) amplifier power claims are more accurate or ‘real’ than modern wattage specifications? There isn’t really any proof of this, but it seems a common thought in many online discussions. It may be due to misrepresentation (outright lies – I’m looking at you 1000W+ mini-systems), misdirection (measurement at distortion at a specific frequency vs the full audible range), or perhaps, simply nostalgia.

Don’t get me wrong, I love good vintage audio gear. But is every piece of audio equipment made before 1980 awesome, while everything afterward is the essence of BPC (Black Plastic Crap)? Of course not. There always is (and has been) good and bad.

Unfortunately, the design aesthetic of pre-1980 silver-faced gear got lost when economic changes forced many smaller companies to be sold to survive, and the design philosophy of ‘more buttons are better’ took over. Digital tuners replaced the old string-driven dials. Heavy aluminum faceplates were often replaced with plastic. Discrete components were replaced with cheaper (and non-user-serviceable) integrated circuits and chips.

Since the basics have changed little in the past 5 decades or so with RCA line-level analog connections, speaker specifications, amplifier power, etc., the vintage stuff really can present a terrific bargain. Where video standards seem to change yearly to keep up with TV changes, plain old stereo music amplification equipment standards have been delightfully stagnant (to the great benefit for us listeners).

There are many very valid reasons that gear made in the 70s and earlier are super collectible and popular right now. Unfortunately this resurgence has greatly increased vintage audio equipment prices, so killer bargains are getting harder to find.

On the other hand, there is a lot of really terrific modern stereo equipment. Most of what you see for amplifiers is multi-channel home theater gear (that is really designed to do just that and not play a 2-channel stereo source). Of course, to meet a price point, certain compromises are made to include 5, 7, or 9 amplifier circuits and multiple sound fields, video scaling, digital displays, etc.

Once you start looking at new dedicated 2-channel music amplifiers, there are fantastic options, but since they are no longer the norm, they tend to be more boutique and expensive.

Not all solid-state or tube amplifiers sound the same, whether they be new or vintage. I’ve gone through phases of collecting and refurbishing vintage equipment and many different brands have been on my workbench and audio rack. What’s remained for daily listening is a lush sounding and exquisite looking Marantz 2245 receiver from the early 1970s serving as a preamplifier for a rebuilt Dynaco ST-35 tube amplifier (designed in the 1960s).

This combo brings joy to my life, was purchased for a song, and is unlikely to ever be replaced.

Remember that a piece of vintage equipment is just that. Vintage, old, and (likely) used. Electrolytic capacitors (inside every audio device) are a solid-state component that changes over time. Even with regular use, electrolytic components fail with age by drying out or leaking electrolyte. This changes the value and function of the capacitor and correspondingly the workings and sound of the equipment (which can possibly fail).

Newer components may well be more reliable over time. The cost of refurbishment and repair should be factored into any vintage component purchase.

3. Speakers and Headphones

Where should you spend the bulk of your money when you buy a stereo system? There really isn’t a definitive rule regarding where percentages should be spent, however, if I had my druthers, I’d say you can’t go wrong with at least 50% of the total budget spent on speakers (or headphones for personal audio).

Speakers and headphones are where the rubber meets the road; they are where electrical signals are transformed into moving diaphragms that shape the sound waves that hit your ears. Speakers and headphones simply make the biggest difference in how a given system sounds and performs.

Admittedly bad recordings or bad playback can never sound perfect, but with typically decent recordings played on properly functioning components, the choice in speaker is what greatly defines the sound of a stereo system.

Tiny speakers are unable to create big, deep bass, although, of course they can be paired with a subwoofer and a full sound can be achieved. There are many different speaker designs and each element makes a difference in the overall sound. Different woofer sizes (which are typically in the range of 6”-12”), different tweeter types (cloth, metal, domed, horn, piezo, cone, ribbon, etc), and the number of drivers (2-way, 3-way, or more) all dramatically impact the final sound.

Headphones also have different driver types including dynamic, piezoelectric, balanced armature, electrostatic and planar magnetic. Each has its own unique properties and distinct sound signature.

Crossovers are an electronic board within the speaker (or multi-driver headphone) that define what audio frequencies are sent to each driver. The complexity, quality, and design of the crossover changes the sound of a speaker. Even the quality of the enclosure makes a difference. Heavy and thick panels tend to make a more solid and less resonant sounding speaker.

So. What’s the best sort of speaker to buy? The answer my friend is not an easy one and is entirely impacted by your tastes, and space you have for them. I used to think I didn’t like any sort of horn speaker (after unsatisfying Cerwin Vega experiences), but it turns out I really like the sound of some Klipsch models. Although brands tend towards similar designs and a ‘house sound’, it isn’t possible to generalize that all speakers from a company will all be of the same quality or sound the same.

Bose has to be the most maligned major speaker brand around; their focus on marketing rather than research has soured many audio fanatics. Although their noise canceling headphones are generally regarded to rank among the best. It is important to remember that whether common or boutique, all brands can make great (and some really not so great) sounding models.

Some speakers and headphones excel at the playback of certain musical styles at the expense of others: dubstep has different requirements than does folk (or country vs rap, or pop vs classical, etc). Some do some things better than others; big deep bass is more important to some ears, others may value huge concert-level volume, or delicate extended highs, etc. Some are more fun-sounding while some are more clinical.

The only way to know what’s best for you is to try to hear as many different options as possible, playing the music that you like to listen to. My current favorite speakers? Refurbished JBL L112s from the late 1970s. They make me smile every time I listen to (and look at) them. You can’t beat that. For headphones, Audeze LCD-2 open-back planar magnetic monsters do most things right for my ears.

Cables

Connecting all those components are cables. A cable is simply a good conductor surrounded by an insulator and terminated with the proper connectors. Easy as that.

Or is it?

Cables are perhaps the most contentious topic in the entire audio hobby (one that, unfortunately, always seems to dissolve into childish name-calling and chest-thumping online).

There is only conflicting information available. Anything from blind tests “proving” the now-defunct Monster Cables are sonically indistinguishable from coat hangers to the coating on the individual strands of wire making dramatic audible improvements.

Manufacturers are often to blame, as the level of rhetoric and outlandish (and unmeasurable) promised improvements go hand in hand with cost. Scientific (and pseudo-scientific) terms such as skin-effect and cryogenic (ultra-cold) treatment may make dramatic, or absolutely no, audible improvements depending on who you ask. Skeptics point towards a lack of blind-testing while supporters passionately tell you about the differences they can hear.

Since this is all for fun (remember?), let’s let everyone do what makes them happy. No need to save anyone from their choices or to convert them to your beliefs.

Cable materials and makeup are often hotly debated. Copper is the most common cable conductor and is rated by its purity, which is expressed in ‘nines’, that is, 99% pure copper. 4-nines is 99.99% pure, while 6-nines is 99.9999% pure, yet it’s almost impossible to measure a difference in conductivity between them. Oxygen-Free Copper (OFC) has been further refined to reduce the level of oxygen in the copper to 0.001% or below.

Just like jewelry, precious metals such as silver, gold, and rhodium all adorn high-end cables. The brightly colored silver is often touted as delivering a brighter (more treble-focused) sound to the music. Is it coincidence, or are our eyes (or expectations) convincing our ears?

Do cables make a difference? I think the answer is ‘probably’, but for most people and most systems, ‘very little’. Buy something that you like the look and feel of and in which you have confidence (placebo effect, or expectation bias, are very much in play here). Don’t buy the cheapest and most poorly constructed junk available and, on the other side, personally, I wouldn’t ever spend a fortune on cables.

Keep cable costs within reason. Make the cable investment a small percentage of your whole system’s cost. That is likely the same percentage of difference that the cables will make in the overall sound.

On the very best and most revealing equipment, different wires may well make audible (if ever so slight) differences. Functioning a bit like a subtle non-adjustable equalizer. But, while sounding different, do they actually sound better? That is in the ear (and in truth, mostly in the mind) of the beholder.

Bargain Interconnects

A change in video standards has had an impact on my traditional recommendation for audio interconnects. Component video cables have been replaced by digital HDMI connections. However, the low capacitance required for video makes component cables perfect for turntables (and every other audio connection).

If you can still find them, I’ve had great luck with surplus higher-end component video cables for connections between audio components. Each set comes with 3 cables (red, green, blue) so 2 video cable sets will yield 3 stereo pairs. Better yet, they can often be purchased for less than $10 from surplus stores.

Speaker Cables

Speaker cables are the final part of the full-sized stereo analog audio chain. Within reason, a bigger diameter wire (smaller gauge number) is better. Thinner wire works fine for short connections (<10 feet), but since it is so inexpensive, plain old flexible 12- or 14-gauge copper wire made up of many tiny strands for flexibility (whether from an electrical cord or actual ‘audio-grade’ wire) will work just fine for most reasonable runs (say less than 100 feet). Don’t cheap out and buy 18- or 22-gauge wire, when thicker 14-gauge is just going to cost a few dollars more.

When the speakers and amplifier allow, I like to terminate speaker cables with gold plated banana plugs for plugging convenience (if the speakers and amplifier allow for that sort of connection).

In general, it is difficult to go wrong if you purchase all your cables from the excellent online retailer Monoprice. Their house brand cables, for everything from speakers to iPhone chargers, are often mentioned as a terrific bang for the buck option. I’ve been impressed with every product I’ve ever purchased from them. The other oft-recommended ‘good’ but ‘inexpensive’ brand is Blue Jeans Cable (although your definition of good and inexpensive may likely vary).

So Now What? Where Do You Go From Here?

Although much of this discussion has been more focused on full-sized stereos, many of the concepts are applicable to headphone audio as well. Amplifiers, cables, sources, etc. are much the same regardless of the size of the playback device.

This discussion is not intended to be exhaustive and to explain every option is beyond the scope of the article. However, I hope that it can serve as a starting point in your own personal audio journey.

Remember, like most things electronic, spending money on audio equipment is an exercise in diminishing returns. Yes, you do have to invest to have a great sounding system. However, pretty quickly after that, good money starts following bad. Upgrades become more and more subtle and more and more expensive.

It’s exciting and fun to chase the ‘perfect sound’; far be it for me to talk you out of the great pursuit. I simply suggest you keep an eye on your budget and buy within your means. The great news is that there are deals aplenty (especially in used gear from other audiophiles climbing the upgrade ladder). I have had great luck with previously owned equipment from CanuckAudioMart.

Whether your budget is astronomical or ever so humble, you can have a great sounding audio system with a little (delightful) work.

ERIC H

November 29, 2020 at 9:01 am

Fantastic article!! Super well done.

Steven Denfeld

January 28, 2022 at 6:21 pm

This is bar none the most effective layman’s explanation of the relationship between wattage and speaker sensitivity I have ever chanced upon. I understand so much now! 🙂