I have an admission to make. I have a pretty manic/obsessive personality. When I get into something, I get into it hard. For a time. And then I get obsessed with something else and move on.

Several months back it was jazz pianists and piano trios. I wrote about it in connection with my experience visiting Jazz Kissa. For about a month prior to and a month after that article, jazz trios filled my Discogs shopping basket, and my listening time.

Of late it’s been bass. I began fixating on jazz’s beating heart in the trios I was listening to, and other albums hitting the decks. Bass is largely overlooked. Bass doesn’t get to solo much (that’s left for the brass and piano). Bass gets lumped in with the “rhythm section” in jazz credits, near the end of the player list, just before the percussion. Bass is the middle child of the Jazz family, outshone by the eldest and out loved by the youngest.

Remove bass though, and things fall apart. Sure, you can replace bass with an organ (and that happened all the time in groups featuring organists such as Jimmy Smith, “Baby Face” Willette and Larry Young), but that low-down, “stealth instrument” of the jazz equation is beyond important.

Jazz without bass is like The Princess Bride without Fezzik. GWB without Dick Cheney. The 1978 Yankees without Thurman Munson.

This is not to imply that jazz bassists are entirely overlooked. Many are stars in their own right. The list of great jazz bassists is long, including: Charles Mingus (or just “Mingus,” possibly the most innovative bass-playing jazz leader and composer); Scott LaFaro, Chuck Israels and Eddie Gomez (all featured in Bill Evans’ evolving trio); Bob Cranshaw (to me the driving force on Bobby Hutcherson’s The Kicker and Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder), Jimmy Garrison (of the John Coltrane Quartet); Jaco Pastorius, Miroslav Vitous and Stanley Clarke (stars in the constellation of ‘70s fusion); and Victor Wooten, Christian McBride, and Esperanza Spalding carrying the bass torch in contemporary jazz.

Bassists I’m particularly drawn to are the infamous Paul Chambers, Ron Carter and Ray Brown, and lesser-known Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen and Isao Suzuki. For the uninitiated, here’s a little something about each of them.

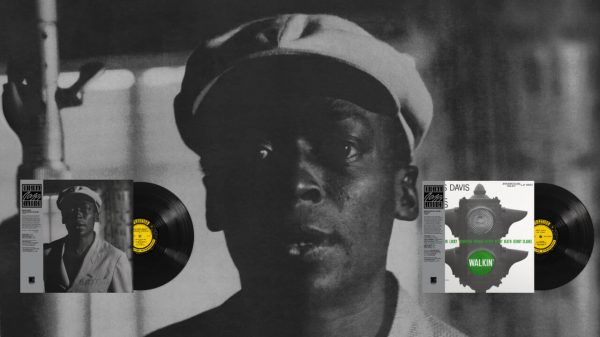

Paul Chambers

Pick up any Prestige, Riverside or Blue Note album recorded in the late ‘50s (and into the early ‘60s), and odds are it featured Paul Chambers. He recorded prodigiously in that time, as both leader and co-leader (check out the magnificent Bass On Top) and sideman. It is mind-blowing the number of sessions he was part of through his 20s, and hard to believe he passed away before his 34th birthday. Though his cause of death was officially from Tuberculosis, alcohol and heroin addiction undoubtedly played their part.

Chambers was a big guy who made a big, swinging sound with interesting basslines. He was known for impeccable timekeeping and an astute understanding of harmony and melody. He was a pioneer of bowed bass in jazz.

Big Paul anchored the first Miles Davis Quintet, was one third of “The Rhythm Section” (as in Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section) with Red Garland and Philly Joe Jones, and played with Wynton Kelly’s fabulous mid-‘60s trio. He also featured on numerous recordings with John Coltrane, Lee Morgan, Hank Mobley and Jackie McLean. Numerous jazz artists wrote songs in homage to him, including Red Garland (The P.C. Blues), Coltrane (Mr. P.C.), Tommy Flanagan (Big Paul), Sonny Rollins (Paul’s Pal) and Max Roach (Five for Paul).

Ron Carter

Ron Carter was originally a classical cellist, giving him a rich stylistic and technical background to draw from. With over 2,000 session appearances to his name, he is the most recorded jazz bassist in history, known for his rhythmic, graceful play and respect for form: whether up or down tempo, on traditional grooves, or playing open forms. As ensemble player he sticks to lower registers to provide a canvas for others, and as soloist is happy shifting up the neck to higher registers to showcase his dexterity and creativity.

Carter came to fame during the five years he spent in the mid- ‘60s with Miles Davis; first in the transitional period between “the quintets,” and then as a member of the second “great” Quintet. When Miles shifted focus to his rock-fusion projects, Carter moved on too as leader and sideman with Creed Taylor’s CTI, in addition to numerous recordings with Miles Davis alumni Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock and Tony Williams.

He is still performing and recording today and is also an active Instagrammer. Carter-led works to look out for include Pastels, Piccolo, Etudes, and the recent live album, Foursight.

Ray Brown

Ray Brown was influenced by Jimmy Blanton and began his career in the ‘40s with Dizzy Gillespie’s band. He made his mark in the ‘50s and first half of the ‘60s as a member of Oscar Peterson’s trios (with various guitarists, and later Ed Thigpen on drums).

Little known fact (at least, not known to me until I started researching): Brown was briefly married to Ella Fitzgerald, who he also backed up musically for a time.

Brown’s tone was warm and well-rounded, and his basslines were precise, soulful, and swinging. He recorded prolifically with credits on 70+ albums as leader and co-leader, well into the 100s as sideman with Benny Carter, Dizzy Gillespie, Milt Jackson, The L.A. Four, Ben Webster and others, in addition to 80+ works with Peterson.

For a taste of his work, check out the live The Sound of the Trio with the Oscar Peterson Trio from 1964 and the duo recording This One’s for Blanton! with Duke Ellington from 1972. Bass players may be interested in his bass-playing text, Bass Method: Essential Scales, Patterns and Exercises.

Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen

Dane Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen (a.k.a. NHØP) picked up the bass at 13, began playing for money at 14, and from 15 was in the house band at the Jazzhaus Montmartre; the main live jazz venue in Copenhagen, and host of concerts through the ‘60s with travelling musicians like Sonny Rollins, Dexter Gordon, Bill Evans, Chet Baker, Ben Webster and Bud Powell, all of whom NHØP supported for shows in Copenhagen and on concert tours across Europe.

In the ‘70s, NHØP was a semi-regular with pianist Oscar Peterson (after the departure of Ray Brown from his trio) on concert tours and several album recordings. As Steeplechase Records house bassist, he also partnered with pianists Kenny Drew (over 50 recordings together) and Tete Montoliu on duo, trio and larger group recordings. Later in his career, NHØP became known and won awards for his original compositions and interpretation of Danish folk songs in the jazz medium.

NHØP displayed phenomenal technique, harmonic awareness and timing. Two fine examples of his work are 1971’s Great Connection with Oscar Peterson, and Chet Baker’s No Problem (with Duke Jordan on piano).

Isao Suzuki

Japan’s grand master and godfather of jazz bass learned to play as a teen on U.S. military bases and went on to lead his own groups in Tokyo in the late ‘60s. He went to New York in 1969 at the invitation of Art Blakey, and worked with the Jazz Messengers, Monk, Mingus, Ron Carter, Wynton Kelly and others before returning to Japan in 1971 when Blakey was arrested entering Canada and charged with drug possession.

Suzuki recorded prolifically in the ‘70s as leader and sideman on the Three Blind Mice label, known for audiophile quality recordings and inventive jazz and fusion. A multi-instrumentalist, he performs mainly on double bass, piccolo bass and cello, but also dabbles in keyboards, guitar and vibes. While in the U.S. he learned engineering techniques from Rudy van Gelder, which he applied to his own recordings on his return to Japan.

He is known for funky, groovy, swinging basslines (both plucked and bowed), and virtuoso merging of classic hard bop with soul jazz and fusion. He is an eclectic personality with a relaxed attitude and penchant for wearing bright colours and skirts onstage when performing.

For a taste of Suzuki’s work, Blow Up (check out the vinyl reissue on Impex) and Black Orpheus are crate-digging grails. Suzuki collaborated extensively with Japanese piano greats Tsuyoshi Yamamoto and Fumio Karashima and made sought-after records with Duke Jordan (Scotch Blues) and fellow bassist Red Mitchell (Bass Club). Unless you’re made of money, you’ll have more luck finding his works on CD than on vinyl, but if you are made of money – be prepared to spend it.

Bass adventures await for the newbie and the vet

New jazz fans will have no trouble finding works featuring Chambers, Carter and Brown, and they’re a great way to learn about and appreciate the contributions of bassists to the best jazz performances. For long-term jazz hands, check out NHØP and Suzuki for some fresh, inventive jazz adventures. Have fun storming the (bass) castle!

Did I miss anyone? Let me know in the comments or message me on @audioloveyyc.

Ron Blomgren

January 16, 2022 at 3:39 am

Great list but you missed a greatly underexposed bassist in Fred Hopkins. Saw him too many times to count and he was a beast. Huge, dark sound and a bounty of harmonic and melodic ideas. Any albums with the Threadgill led trio Air are recommended but especially Air Lore where the band masterfully re-imagines Joplin & Morton

Eric Pye

January 16, 2022 at 5:54 pm

Will have to check that out. Thanks for the heads up, Ron.