I’ve been writing about music for decades, but I still can’t tell you when I can share part of a song for educational purposes.

This isn’t because I’m lazy or stupid. The plain truth is nobody can answer this question.

That seems crazy, no? Music is a huge business, and the offices of record labels are teeming with copyright lawyers. Surely they must have published some rules or guidelines about this matter?

But I’ve never been able to get a straight story from an expert about ‘fair use’—which is the legal term that describes situations when a person can share part of a copyrighted work. Heaven knows, I’ve tried to get answers. After all, I’ve written music books for major publishers, and have repeatedly sought their legal guidance on this very matter. The sad fact is that they don’t know what’s allowed and what isn’t.

Consider the plight of music education channels on YouTube. They fill an important role in the music ecosystem, but the record labels operate a nonstop war of legal intimidation against them. Recently Rick Beato shared a video on songs with unusual time signatures—and was careful to limit himself to 10-20 seconds of the songs he discussed. His entire educational video was just 11 minutes long, but he got 16 demonetization complaints from record labels in response.

“This video is a promotional video for these songs,” Beato remarks, “because the whole idea of making these videos it to bring people in and then expose them to artists that they haven’t heard before.”

It couldn’t be more obvious that these labels benefit from Beato’s advocacy—yet they harass him. And they do the same thing to countless other music educators. Here’s Adam Neely’s response to the situation, with the rightfully sarcastic title: “What I Want to Teach, But Can’t, Thanks to Universal Music.”

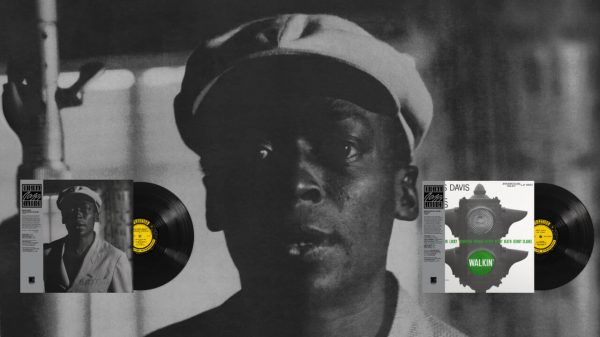

He shares the story of Universal Music filing a complaint about Beato’s use of a John Coltrane song—when it was actually Miles Davis’s recording of Sonny Rollins’s “Oleo.” I might laugh at the idea that a major label issues legal threats on songs but can’t even identify the name of the recording artist, but the anecdote is too depressing to elicit more than a bitter chuckle from me.

Many of you will be puzzled by this. Adam Neely has 1.5 million subscribers. Rick Beato has 3 million subscribers. You might think labels would support these influential educators who get music fans excited about John Coltrane or Miles Davis—and let this new audience hear a few seconds of music. But they won’t.

And why? Because they can make some immediate cash by ‘demonetizing’ a music education video, and seizing the income Beato and Neely would otherwise earn. Instead they suck that cash into their own coffers.

Hey, these labels need the money to keep all those lawyers on the payroll.

Can Beato fight it? After all, these 16 legal claims against his video seem rather dubious, and there is an appeal process. But here’s where it get interesting—and very revealing.

Beato explains the Catch-22 in succinct terms: “If I disputed every one of them, there’s no chance I would win every one. I could lose 15, and have one of them say that they still uphold the claim—and that one artist would get all of the money from the video instead of the 16 people splitting it up 16 different ways.”

Do you appreciate how dysfunctional this is? The system actually incentivizes copyright holders to be as unreasonable as possible, because the bigger jerks they are, the more cash they collect. And the record labels who act fairly merely end up making more money for those who don’t.

And that’s why this problem won’t get fixed. Not today, not tomorrow, not ever. The record labels could easily issue guidelines—stating how many seconds of music (or what percent of a track’s entire duration) can be used for educational purposes. But they won’t.

Because that would eliminate this whole shakedown process. The current system—broken and incoherent—is much better for the record labels. The last thing they want is a clear, fair, and transparent process.

Let me give you an analogy—which is also a puzzle for you to solve:

Back in the days of the Soviet prison camps in Siberia, the inmates were allowed to go outside for brief spells—and many would gather up any spare sticks or branches they could find. They needed these to make small fires to keep themselves warm during those bitter winter nights.

Before returning to the camp, the guards would search the inmates, and confiscate the wood. The guards would then use the wood for their own fires. But the guards didn’t confiscate the wood every day—they only did it around half of the time.

Here’s the puzzle: Why did the guards forget to search the inmates on so many days?

The answer is simple economics. If the guards had confiscated the wood every day, the inmates would soon stop collecting it. That would hurt the guards because they wanted those sticks and branches for their own fires. The end result was perfectly logical: the prisoners needed to have some hope of keeping their wood, and so a system arose with (1) no clear rules, (2) no predictable outcomes, (3) and rewards going to the bullies who are the best at bluffing and intimidation tactics.

Now do you understand why the music industry will never allow for clear rules on fair use? They are like the guards in the Soviet gulag—they earn more by forcing others to take risks and punishing randomly. That’s exactly how they maximize their sticks and branches—or, in this case, their IP cash flows.

But the reality is that they only earn more in the short term. It’s obvious they would make much more money in the long term by supporting music educators who are developing the next generation of music lovers.

But lawyers don’t think that way.

Many people in media are angry about this. I even had an editor ask me to write a book that would ‘test the limits’ of fair use—but I said no. For the same reason, you won’t hear any recordings on my music education videos. It’s also why I turn down educational organizations that ask me to give video lectures on the history of jazz. I know this could have a significant impact in expanding the audience for this music, and that’s one of my key life goals. Yet I have no choice: I have to say no.

I have zero interest in breaking the law, or trying to find how much I can bend it. And I refuse, on principle, to battle with record labels for permission to build their customer base.

But it would help if someone could tell me what the law actually says.

Do you think I’m exaggerating? Try researching this subject and see for yourself. For example, go to an expert—in this instance let’s consult a website with the promising name of www.copyright.com. Hey, you should be able to get some details on copyright law there, no?

But here’s what they say:

“Fair use is an exception to copyright protection (or, more accurately, a defense to a copyright infringement claim) that allows limited use of a copyrighted work without the copyright holder’s permission.

“This might appear simple, but the truth is: fair use is very subjective. It’s so case-specific, in fact, it’s decided on a case-by-case basis. There might be situations or circumstances where using music in training materials has some credible fair use arguments. However, those situations are likely to be very narrow.

“If you’re going to rely on fair use, the bottom line is, you need to factor in how much risk you’re willing to take. Why? Because some uses are riskier than others and the risk of a failed fair use defense is copyright infringement.”

Put simply, trying to operate within the law is like going to Vegas and playing the slot machines—you need to consult your own risk profile. But that’s not law; instead it’s what philosopher Thomas Hobbes called the State of Nature, a brutal world before the first laws were made. In those dangerous situations, our social life is an anarchy where there’s no clear right or wrong. People take what they can get, and might makes right.

Surely our copyright law should be better than this?

You might think that legislators would step in at this point. And they could—they could pass a law tomorrow allowing educators to use a specified percent of a recorded track, or a certain number of seconds. But they won’t.

Well, maybe if educators got together and spent millions on lobbyists, they could get that done. In fact, I’m certain that this law could be passed quickly if music teachers had access to the same lawyers and lobbyists as do the major labels. But what educator has that kind of cash?

That doesn’t mean there won’t be a loosening of copyright law. But it will only happen to reward Silicon Valley—which, depending on the day of the week, sometimes wants loosey-goosey copyright laws. But these changes in IP law will have nothing to do with fairness or helping the music ecosystem. Limitations on copyright thuggery will only be a side effect of something that benefits Google or Facebook or some other tech titan with supersized influence in DC.

I know this sounds cynical, but I’m just telling it to you straight—in a way that few people do when discussing music copyright issues. The blunt truth is that different interest groups are battling over these matters, but no one with any genuine power is working for the benefit of the music culture at large.

The combatants are huge entertainment corporations, large investment groups who own publishing catalogs, and enormous web platforms. People sometimes ask me to identify the heroes and villains in these legal maneuverings, and they get frustrated when I say there are no good guys in the fight. We can merely try to pick the lesser of (more than) two evils.

But a few things are certain: (1) The system is broken; (2) The organizations with money and power don’t want to fix it; and (3) The culture at large is hurt because education and advocacy programs—absolutely essential to the future of the musical arts—are punished rather than supported.

Maybe the next time a major label honcho gets interviewed by a fawning journalist, this matter can get raised. And for fun, let’s also see if the label CEO can tell the difference between Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

Ted Gioia is a leading music writer, and author of eleven books including The History of Jazz and Music: A Subversive History. This article originally appeared on his Substack column and newsletter The Honest Broker.

ORT

July 3, 2022 at 2:05 pm

“The first thing we do, is force all the lawyers to listen to cRap music.”

Well written, sir.

ORT

ORT

July 3, 2022 at 2:37 pm

I forgot to ax, does de minimis not exist in law? Surely it must for ’tis painfully obvious that de stupidous does.

Again, well written sir.

ORT